The Bhagavad-Gita: Righteousness or Duty?

The relevance of the father of the atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer, and his famous quote from the Bhagavad-Gita bring up question of duty vs. righteousness in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

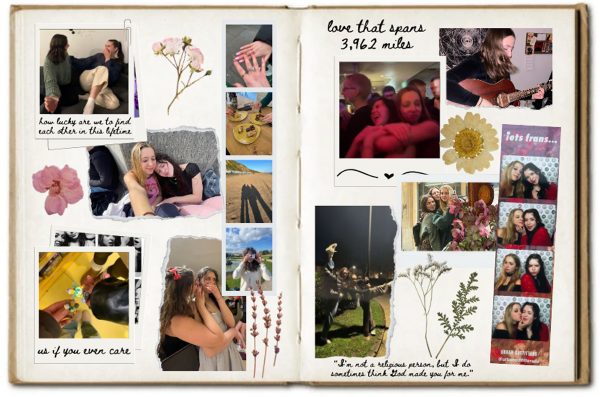

Photo by Submitted

On July 16, 1945, nuclear weapons were tested for the first time in the New Mexican desert. A month later the atomic bomb would be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the aftermath of which would turn the tide of the war in favor of the allies.

The father of the atomic bomb, Robert Oppenheimer, would recall seeing that first test explosion for the press twenty years later in a quote that would become one of the most cited and least interpreted quotations from the atomic age.

“We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most were silent,” Oppenheimer said, according to Wired magazine. “I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”’

Oppenheimer’s sinister interpretive quote, “I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.” would forever become synonymous with the atomic bomb whose repercussions were still rippleing across the post-war nation.

Oppenheimer first read the original Sanskrit Bhagavad-Gita when he was a teacher at Berkeley in the 1930s.

According to his colleague, Isidor Rabi, this manifested in him, “a feeling of mystery of the universe that surrounded him like a fog.”

The resulting aftermath of the United States’ “necessary” dropping of not one but two atomic bombs on Japan remains a heated matter of debate. Oppenheimer would go on to become an advocate against nuclear weapons describing himself to former President Harry Truman as having “blood on his hands.”

Oppenheimer was never quite able to come to terms with his misgivings about bestowing humanity with the means to annihilate itself. It was then that Oppenheimer turned once again to the Bhagavad-Gita for understanding.

The Bhagavad-Gita, which translated to “Song of God” in Sanskrit, is a 700-verse Hindu poem that recounts a conversation between the kshatriya (warrior) Prince Arjuna, a descendant of the god Indra, and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of the god Vishnu.

The story takes place in a war-torn land. The protagonist, Prince Arjuna, is on the precipice of a great battle between an opposing army that contains members of his family and friends. Arjuna wavers on his next decision and on whether to kill his kin.

Arjuna ascertains that he cannot bear to kill his cousins, which he fears would destroy his family’s dharma (holy duty). Arjuna mentions his reservations about the justice of killing his loved ones, to his charioteer Krishna.

Krishna responds by scolding Arjuna for his “cowardice.” He lectures the warrior prince on the Hindu fundamental truth, that people’s souls don’t cease to exist after the death of their bodies.

He explains that the eternal souls of Arjuna’s loved ones will be reincarnated in new bodies, therefore Arjuna should not grieve for those who will be killed instead he should follow his dharma as a kshatriya and fight.

The essence of Krishna’s reply is that with the right understanding, one does not need to renounce actions, one must only renounce the desire (karma) for the result of the action (fruits of actions). Therefore acting without desire is the key to salvation.

By the 11th verse, both men remain at an impasse, Arjuna asks Krishna to reveal his true cosmic nature in a last-ditch effort to understand Krishna’s viewpoint. Krishna obliges and transfigures into his godly doomsday embodiment—he transforms into a form with a fiery mouth, innumerable eyes and limbs that seem to contain everything in the universe.

In this new form, Arjuna finally understands. Krishna is the source of all things, both physical and metaphysical. He is the highest mountain, the deepest valley and he is the greatest god, containing all the gods within himself. He is both the creation of everything and its dissolution.

It is here that Oppenheimer reaches an epiphany.

Oppenheimer concluded in regard to his creation and subsequent role in the bombings on Japan, that he had had a job to do, a duty just like Arjuna. He had to do his job, not because of the results but because doing his duty would bring serenity to his discontented existence if the fundamental teaching is to be believed.

In Oppenheimer’s interpretation, the word that he speaks as “death” refers to the original literal translation “world-destroying time.”

The Bhagavad-Gita teaches that irrespective of what Arjuna does, everything is out of his hands and instead in the hands of the divine.

Today, 77 years after the first nuclear weapons experiment, the ethical question of if and how our actions impact the world around us remains.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Bhagavad-Gita’s relevance on the question of whether to do one’s duty or follow the path of the righteous makes its way back into the subconscious.

Every day more and more Ukrainians are taking up arms against their invaders, on the other side, Russian soldiers are marching to their neighbor’s border to fulfill their own duty.

Whether following one’s duty past the point of no return is worthier than one abstaining from action for righteous reasons is up to everyone’s interpretation.

For Oppenheimer to accept his role in the devastation that took place in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, perhaps he had to believe that it was out of his hands. But at what point should righteousness outrank duty? When does doing the right thing triumph over obligation?

Hinrichs can be reached at [email protected].

Allison Hinrichs is a third-year journalism and multimedia communication student. This is her fourth semester at The Spectator. Allison loves being outdoors and anything that gives her an adrenaline rush. She loves hiking, rock climbing, snowboarding and photography.

P Paul • Aug 19, 2022 at 3:31 pm

“The essence of Krishna’s reply is that with the right understanding, one does not need to renounce actions, one must only renounce the desire (karma) for the result of the action (fruits of actions). Therefore acting without desire is the key to salvation.”

…one does not need to renounce actions (karma), one must only renounce the desire (fruits of actions) for salvation. And, that is when you say it right, “Therefore acting without desire is the key to salvation.”

David Sawyer • Jul 28, 2022 at 7:44 pm

Thank you for this well written and thought-provoking article. Everyone interested in current events, in Ukraine and now in Taiwan, would do well to read the Bhagavad-Gita. I recommend the “As It Is” translation with helpful explanations, by His Divine Grace, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada.