Customs lines in O’Hare airport unacceptable

My lengthy and unsanitary journey out of the airport

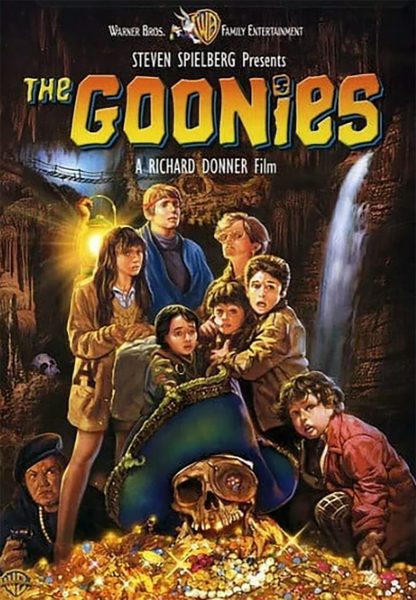

Photo by Lea Kopke

A mass of people filled the entrance to Terminal 5 on March 14 in the Chicago O’Hare International Airport.

On March 12 I received the news from UW-Eau Claire that my study abroad program was being cut short due to COVID-19.

Because of this, a short two days later I boarded a flight back home. I thought my living nightmare was being sent home, but little did I know what horrors awaited: a six hour wait in the Chicago O’Hare International Airport.

Around thirty minutes before my plane landed an announcement came on regarding the procedures passengers needed to go through upon landing.

We were told U.S. citizens did not need to fill out a customs report, but there would be additional paperwork and a screening given out by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention once we got through customs.

There we would also learn about the virus and the CDC’s recommendations regarding self-quarantine.

The short speech seemed rambly, but everything seemed in order.

At around 4:45 p.m. I got off the plane and made my way out of the gate and into Terminal 5 (the international terminal). As I rounded the corner I was greeted with a mob of people.

There were no clear lines as people attempted to be the first down the escalators into the terminal, elbows high and brows furrowed.

At this point I still was not too concerned, as I figured several planes had landed at the same time and caused the congestion.

As I got to the escalator, though, the reality of the situation sunk in.

The entirety of the area below, a dome shaped room before a hallway, was filled with a mob of people, each no more than a few inches apart from one another.

As I stood there I bumped into a man and joked, “Well if we didn’t have the coronavirus before, we sure all have it now.” Eventually an airport employee began to shout over the crowd.

He told us everyone needed to fill out a customs form — which was passed through the crowd, helping to spread germs — and try to get into a line on the left side of the room so that travelers from non high-risk areas could get through. He also tried to convince the crowd not to take photos because, he said, “some people might not want to be in them.”

I chatted with the man I had met — Evan — to pass time, as there was no internet connection or phone service. He was an astrophysics grad student who was sent home from his research trip in Sweden.

Around 6 p.m. we had finally made it down the line enough to see around the next corner. Again, the hallway was crowded with people. A worker stood, offering free waters to everyone.

Halfway through the area a line started on the other side of the hallway. An older man in the line told Evan and I that it took him two hours to get from our point to his.

We laughed it off, thinking he was clearly exaggerating as he complained. It turns out he was right.

As we rounded the next bend you could see into the customs room. Hundreds of people were crammed into lines snaking through the entirety of the area.

As you entered the room workers handed out snacks and health history sheets, but did not offer any hand sanitizer.

There were no signs telling us where the lines were leading to, or what to prepare for at each of the two stations. It took an hour of waiting before I made it through customs.

As I walked through to get to the next line I spoke with one of the airport workers. She told me she’d been at the airport since 6 a.m. but was not too bothered because she was getting paid overtime, which would help her in the coming weeks when her hours would probably be cut.

I headed back into the snaking line with Evan around 7:30 p.m. and it would be two hours until we would make it to the next station.

We chatted with an elderly missionary couple who was in line next to us, at least until the woman had to find a place to sit down due to exhaustion.

At this point people around me were getting more and more anxious. People were missing their connecting flights, despite security reassuring the crowds that the airport was aware of the situation and would wait for its passengers. At this point some had resolved to just getting a hotel and booking a flight the next day. Evan was one of these people.

At around 9:30 p.m. we hit the next round of counters. There we handed our health sheets, which asked about where we had traveled and if we had any symptoms, to workers who typed in our contact information.

I overheard two of the workers complaining to each other under their breaths. They wondered when they would get to go home and at what point they could just leave without asking.

Next I was brought into one final line that led to the CDC screening area. In that line I saw the worker I had spoken with earlier: she had now been in the airport for 16 hours and had still not been told when she had been relieved.

At the front of the line I gave my documents to a worker, who handed myself and the documents off to a second worker, who guided me to a third worker who was to do my screening (not confusing at all, right?).

There I had my temperature taken and was asked if I had shown any symptoms. I did not, so my documents were stamped and I was free to go retrieve my luggage.

When I left the airport, it was a little past 10 p.m., five and a half hours after I had landed.

While I could complain about my own woes of being squished into tight spaces with other potentially sick international travelers, or not getting a chance to sit down after being awake for over 24 hours, the real issue here lies in how people as a whole were treated throughout this experience.

Not one time did I see an opportunity given for the elderly or families with young children to get a fast pass through the lines.

They stood, along with everyone else, for the six hours it took to make it out of the terminal.

These conditions are ridiculous and unfair for those living in demographics that have been proven to be more susceptible to the virus.

In addition to being unorganized, the airport was also uninformative.

At no point did anyone tell me information regarding how to self-quarantine when I got home, or what symptoms I should be looking out for.

Besides the graphics thrown up onto the televisions in the room, there was no advice given.

The governor of Illinois, J.B. Pritzker, and the O’Hare airport itself took to Twitter late Saturday night to voice their opinions on the situation.

“The crowds & lines of O’Hare are unacceptable & need to be addressed immediately,” Pritzker wrote. “@realDonaldTrump @VP since this is the only communication medium you pay attention to—you need to do something NOW. These crowds are waiting to get through customs which are under federal jurisdiction.”

The O’Hare Airport replied to several twitter complaints with a response that also asserted the delays to be the fault of the federal government.

“Thank you for yr patience,” the tweet said. “Customs processing is taking longer than usual inside the Federal Inspection Services (FIS) facility bc of enhanced #COVID19 screening for passengers coming from Europe. We’ve strongly encouraged our federal partners to increase staffing to meet demand.”

While the wait times have since been improved, there is no reason thousands of Americans should have been shoved into such tight quarters and long lines in the first place.

It was clearly an environment that put people at risk of contracting the virus and worsening a pandemic that has already begun to shut down the country.

Kopke can be reached at [email protected].

Lea Kopke is a fourth-year journalism and German student. This is her seventh semester on The Spectator staff. She plays the clarinet in the Blugold Marching Band and recently relearned how to ride a bike with no hands.

jan miszewski • Mar 24, 2020 at 7:27 pm

we were in the line sat 14th p.m. after arriving from london. a group of 4 of us travelling together, we were yelled at told not to video stuff but were also given water and food , cookies and jerky for 5 hours as we went through the line. the only exta stuff done was temperature measurement and data collection. people older than us (65+). young children and people in wheel chairs also got the 5 hour treatment. we were encouraged to take our temps daily after getting home this we did in the 18th three of us had temperature that climbed over 100.4 so we got tested in mason city iowa morning of the 19th . on sunday we were told we were positive for covid 19. we left from my sisters house in nottingham on the 13th they have no symptoms so its clear we got it in the ohare line. (so unneccessary)