Mental health in isolation

Increase in eating disorders seen during COVID-19 pandemic

More stories from Grace Olson

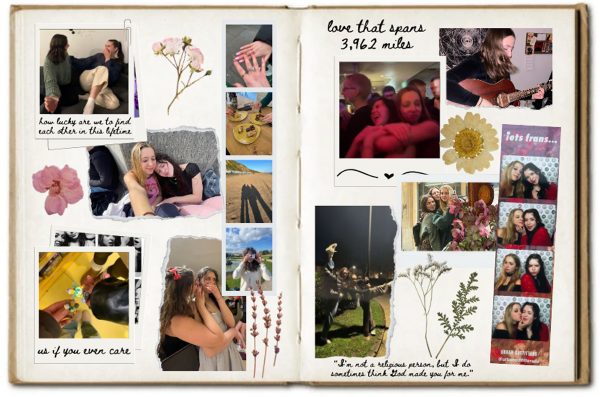

Photo by Bethany Mennecke

Welcome to another “Mental health in isolation”. I can’t believe the semester ends next Friday — I feel like we just started our third semester of quarantine school.

As excited as I am for summer, there is a slight sense of panic as I graduate this December and that means I’m one step closer to life without having school as my main priority.

I have tried to deal with this panic and end of semester stress healthily, like by giving myself time to rest and recharge, and remembering the bigger picture — of graduating — and of all of the hard work I’ve put into school so far.

This is hard. It’s hard to not just blow off homework or not go to class, and a mental illness or disorder on top of that makes it that more difficult.

One example of a mental illness that often happens out of stress is bulimia.

According to Mayo Clinic, bulimia is a serious potentially life-threatening eating disorder. Individuals with bulimia might secretly binge and then purge to get rid of the calories.

Someone with bulimia may have different ways to get rid of the calories. One may self-induce vomiting or misuse laxatives, weight-loss supplements, diuretic or enamas after binging.

Someone with bulimia may be preoccupied with their weight and body shape. They may judge themselves very harshly for their self-perceived flaws.

Some symptoms of bulimia symptoms include:

- Being preoccupied with their body shape and weight

- Living in fear of gaining weight

- Eating abnormally large amounts of food in one sitting

- Having a sense of loss of control during a binge — like they can’t control what they eat or how much

- Forcing themselves to vomit or exercising too much

- Fasting, restricting calories or avoiding certain foods between binges

While the exact causes are unknown, the common factors in the development of eating disorders include genetics, biology, emotional health and societal expectations.

According to Medpage Today, psychologists, nutritionists and primary care providers said they have seen higher cases of eating disorders and referrals to eating disorder treatment centers since the start of the pandemic.

Cynthia Bulik, founding director of the University of North Carolina’s treatment center, said they can’t provide enough services because the demand is so high.

And this problem isn’t just at UNC.

Before the pandemic, clinicians at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., said they once saw five to six patients each day for an eating disorder, but by the end of fall of 2020 had seen that number double.

One estimated cause of this increase comes from children’s separation from friends and family and the lack of structure during quarantine.

Teenage years are already confusing enough, so adding a national pandemic on top of that is bound to create some issues.

Stephanie Zerwas, an associate psychiatry professor at UNC Chapel Hill, said the uncertainty and constant pressure from increased engagement with social media were a huge amount of risk factors placed on young people.

To contact the National Eating Disorder helpline call (800) 931-2237 from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Monday through Thursday and 11 a.m. 5 p.m. on Fridays.

For crisis situations, text “NEDA” to 741741 to connect with a trained volunteer.

Olson can be reached at [email protected].