History professor emeritus addressed apportionment through the ages

Bob Gough discussed the Apportionment Act of 1792 on Monday night

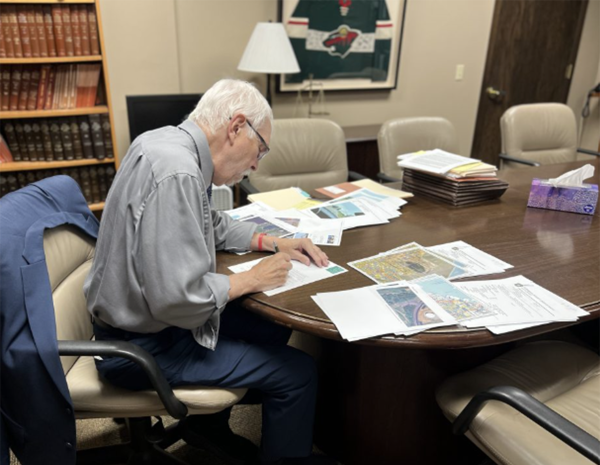

Photo by Sam Farley

Bob Gough, professor emeritus of history, taught an audience about the Apportionment Act of 1792 and its modern-day implications during his presentation on Monday night.

The apportionment of representatives in Congress was a tough task in 1792 and still continues to stump lawmakers today, said Bob Gough, a professor emeritus of history who taught at UW-Eau Claire.

Gough provided historical context to today’s Supreme Court case concerning gerrymandering, Gill v. Whitford, by sharing the storyline of the Apportionment Act of 1792 in his talk entitled “Making the Constitution Work.” Gough spoke on Monday evening in Centennial Hall.

Apportionment refers to the process of allocating the representatives a state receives in the House of Representatives based on state population.

“The Apportionment (Act) of 1792,” Gough said, “has implications for apportionment now.”

The Constitution is ambiguous when it comes to apportionment. Gough said this led to “not a full understanding or full perception of representation in Congress.”

Specifically, the size of Congress is not determined in the Constitution, and it is not clear exactly how equal proportion would be calculated.

It was this ambiguity which led to the debate surrounding the first apportionment of Congress in 1791. After a census counted 3 million people in the United States, the legislatures decided there would be one representative for every 30,000 people.

Congress erupted in a debate that was primarily divided between “Northern” and “Southern” states, Gough said. Northern states preferred a smaller Congress while Southern states wanted a bigger Congress. Both sides of the issue found their respective motivations rooted in want of more representative power, Gough said.

Fisher Ames, a representative from Massachusetts, led the charge for the smaller states. Using a method of apportionment that seemed to favor — according to James Madison— the New England states, Ames increased the number of representatives in the House from 65 to 112.

Madison, an advocate for a bigger Congress, was against Ames’ proposal. He claimed the methods Ames used to divide representatives was unconstitutional because it divided the population at a national level instead of at a state level, therefore ignoring state entities.

Ames’ first proposal never came to vote. Instead, the House temporarily adopted the Senate’s method for apportionment, which drew a lot of similarities with Ames’ proposal, in March 1792.

“I can only speculate that that was to break the stalemate,” Gough said.

Later, Congress’s second apportionment bill was vetoed by President George Washington on April 5, 1792.

Acting quickly, Gough said, Congress drafted another bill that called for one representative for every 33,000 people and changed the total number of seats to 105.

This bill passed and became the Apportionment Act of 1792 on April 9, 1792. The Act set the stage for future debates about representation — methods for apportionment have been changed several times over the years.

Currently, Gough said, the United States uses the Huntington-Hill method, which was developed in 1940 by a panel of mathematicians and scientists. Gough said the method relies on geometric means.

Bridget Brownell, a UW-Eau Claire student, said she could imagine that apportionment was a “very confusing” issue to tackle.

Madeline Post, another UW-Eau Claire student, agreed with Brownell, adding that the “ambiguity in the Constitution” lead to the confusion.

Post said she found value in discussing “how the people who actually went to the Constitutional Convention envisioned how it would be proportioned.”

There are traces of history in today’s court case, Gill v. Whitford, Gough said. Historically, party politics have taken a role in apportionment. Gerrymandering, Gough said, is an extreme example.

“They can’t expect perfection,” Gough said.

He said there isn’t a clear solution for apportionment in 2017. Apportionment challenged American lawmakers in 1792 and will continue to stump them in 2017.

Neupert is a fourth-year journalism student at UW-Eau Claire. She is the executive producer of Engage Eau Claire on Blugold Radio Sunday. In her spare time, Neupert's working on becoming a crossword puzzle expert.