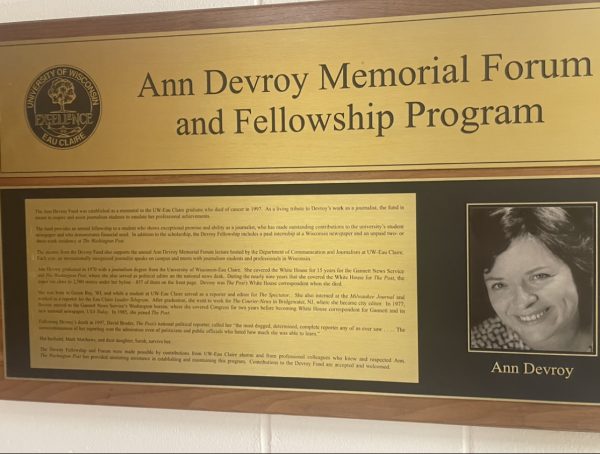

Alum’s research on Steamboat Geyser receives national attention

A long-time “geyser gazer,” Mara Reed explored why the world’s tallest active geyser started erupting in 2018

More stories from Ta'Leah Van Sistine

Photo by Mara Reed

Steamboat Geyser is the world’s tallest active geyser and after it erupts, “vigorous steaming” occurs for several hours, Mara Reed, a UW-Eau Claire alum, said.

Huddled on platforms throughout Yellowstone National Park, a community of watchers — patient observers — wait for an eruption with their eyes fixated on the geyser in front of them.

These individuals, known as “geyser gazers,” have a “keen interest” in geysers and often record the timing of geyser eruptions.

Mara Reed, a UW-Eau Claire alum, is one of them.

At six years old when she visited Yellowstone for the first time, Reed said she remembers watching the geysers — something she continued to do whenever she returned to the park.

“Through just kind of sitting and waiting with (geyser gazers), making friends with a lot of them, I guess the love sort of grew exponentially from there,” Reed said.

Her passion has resulted in research published in early January on why Steamboat Geyser in Yellowstone began erupting more frequently again in 2018.

What makes Steamboat tick?

Before March 2018, Steamboat’s last active phase — or “prolonged series of major eruptions” — was from January 1982 through September 1984, according to the article Reed and ten fellow scientists authored.

Before January 1982, early 1969 was the last time Steamboat was in an active phase. While Steamboat would erupt a couple of times between active phases, most of its recent eruptions that were analyzed for Reed’s study occurred less than 10 days apart, she said.

“Steamboat Geyser is kind of the holy grail of geyser gazing,” Reed said. “It’s a geyser I never thought I’d have the chance to see.”

Reed’s research garnered national attention from newspapers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal for its attempt to answer the question, “Why did Steamboat start erupting in 2018?”

“It was interesting because that was the (question) we had the most ambiguous conclusions for,” Reed said.

One idea Reed and her team found some evidence for was that an uplift, or an elevation of Earth’s surface, occurred before Steamboat started erupting in 2018.

When considering whether the uplift caused Steamboat’s most recent active phase, Reed said her team didn’t accept or reject the hypothesis because it wasn’t clear why other Yellowstone geysers wouldn’t have been affected by the uplift.

Earthquakes were also dismissed as the potential cause of Steamboat’s active phase because while they’re known to affect geyser activity, Reed said none of the earthquakes before March 2018 were strong enough to trigger Steamboat.

“We were able to rule out some things, but in general, we don’t know,” Reed said.

The second question explored in the article had to do with the factors controlling Steamboat’s intervals, or the periods of time between each eruption.

Reed said seasons affect the intervals, so they are longer in the winter and shorter in the summer.

The final question in the study asked why Steamboat — the world’s tallest active geyser — is so tall. Reed said it’s because water is stored deeper at Steamboat than at other geysers, so more energy can be used to power its eruptions.

“The best part of this research was we went to Yellowstone, and then we sat by Steamboat and we waited,” Reed said, “and of course, you’re focused on your research work when finally the geyser actually erupts.”

Research roots at UW-Eau Claire

During one visit to Yellowstone, when Reed was in the midst of applying to colleges, she met a fellow geyser gazer who happened to be a mathematics professor at UW-Eau Claire: Vicki Whitledge.

Reed said Whitledge encouraged her to apply to UW-Eau Claire and after researching the university further, she thought it was a great fit for her.

The first research Reed conducted on Yellowstone’s geysers was done alongside Whitledge when she eventually became a physics student and a Blugold Fellow at UW-Eau Claire. They worked on a statistical analysis of the intervals between eruptions for certain geysers.

Every year, 20 first-year students are offered the Blugold Fellowship, a two-year program that includes a scholarship and a stipend. As Blugold Fellows, students work with university faculty on projects and collaborative research about topics that can be within or outside their areas of study.

After working with Whitledge for a semester, Reed then started writing a proposal to the National Park Service to have temperature loggers placed in geyser runoff channels, so they could be monitored.

Matt Evans, the director of the Blugold Fellowship, became a mentor to Reed throughout her time at UW-Eau Claire, she said.

Evans said Reed’s Blugold Fellowship research on Yellowstone’s geysers proves how students can explore what they are passionate about and consider whether it’s something they would like to pursue after they graduate.

When Evans saw Reed’s name mentioned in The New York Times’ article about her research, he said he was proud to see a student who he advised and supported “make it in the big time.”

“For those four years that they’re on campus, we (faculty) learn who they are and we help them get to where they think they want to go and then we release them,” Evans said. “And so when we see their names, there’s always this inner joy that comes out that makes you feel like you were a small part of something that allowed someone to reach larger goals.”

Scott Clark, an associate professor of geology at UW-Eau Claire, also served as an academic mentor and advisor to Reed, and he said he’s impressed that Reed was listed as the first author for her Steamboat research after just graduating from UW-Eau Claire in 2018.

“It is especially impressive that she published her research in a journal as prestigious as the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,” Clark said.

How the Steamboat research started

After finishing a full year of her earth and planetary science graduate studies at the University of California-Berkeley, Reed attended the 2019 Cooperative Institute for Dynamic Earth Research summer program.

There, students and early career researchers can learn from each other and develop potential research ideas, Reed said.

Before attending the program, Reed said she had already conducted some independent research on Steamboat, but there were more aspects of the topic she wanted to pursue.

Researchers at the program broke out into small groups, and when Reed shared her idea of studying Steamboat, she said she was surprised by how many people were interested and wanted to pursue the research.

“Sometimes people will attend the program and the research kind of doesn’t go anywhere,” Reed said, “but what was so neat about our group is that we obviously continued our collaboration and it ended up all the way into a manuscript.”

Almost all of the people in Reed’s group, in addition to a few others who joined the research later on, became co-authors for the article on Steamboat, Reed said.

‘It’s truly larger than life’

As people continue to reflect on the mystery surrounding Steamboat, Reed said she is currently working with United States Geological Survey scientists to study how hydrothermal activity affects trees.

Geyser gazing for Reed, though, remains her passion, and watching Steamboat erupt is still “an incredible experience,” she said.

Steamboat is loud when it erupts, Reed said, so even if a person is standing next to you and is trying to have a conversation, you might not be able to hear them. But, no matter, all eyes remain focused on the geyser, tracing it as it travels toward the sky.

“There’s just suddenly this huge wall of water that starts building and it keeps going higher and higher and higher and suddenly you realize that you’ve craned your neck all the way back and you still can’t see the top of the water,” Reed said. “It’s truly larger than life.”

Van Sistine can be reached at [email protected].

Matt Evans • Feb 4, 2021 at 11:52 am

It is always exciting to read about how UWEC students have used their talents beyond UWEC.