Get depressed, drink massive amounts of alcohol. Get angry and sour, drink some more. Rinse and repeat. Such is the life for the men who were laid off from the shipyard and now spend their Mondays in the sun, instead of working. The cyclical nature of life and their current predicament is the main focus of the 2002 Spanish film, “Mondays in the Sun.”

In the film’s opening, calming music drones in the background of a directly contrasted foreground of workers protesting with the police. After the protest and its repercussions are said and done, the audience comes to focus on a half-dozen of the laid-off workers.

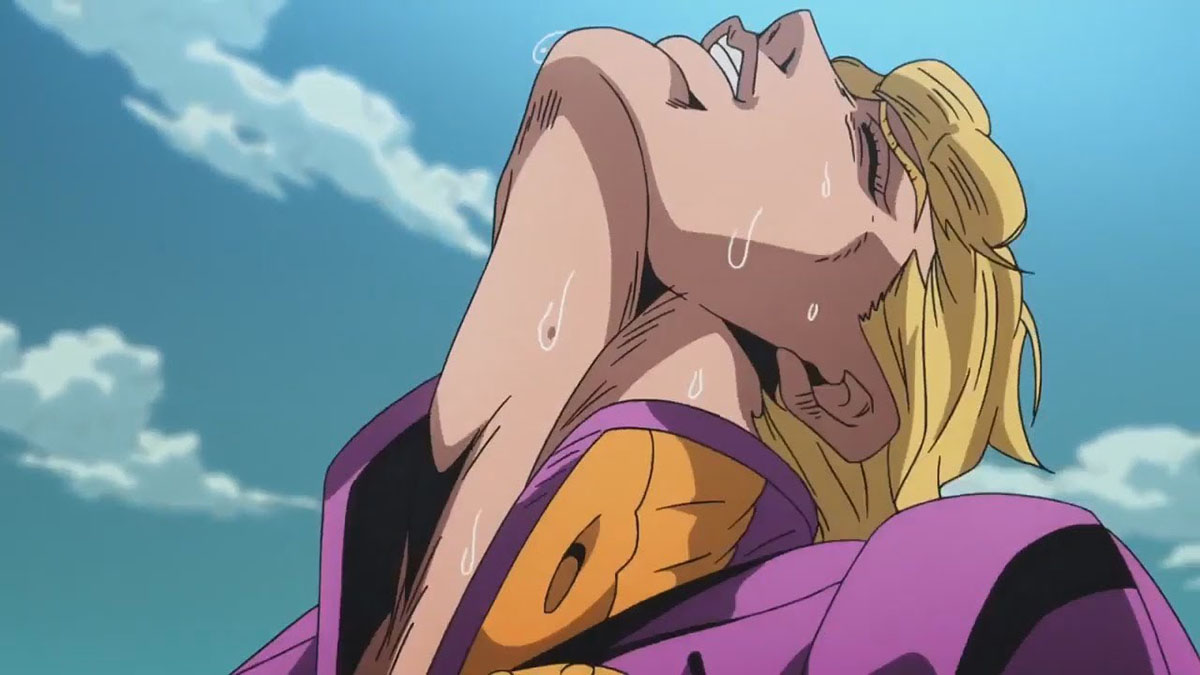

At the group’s center is Santa (Javier Bardem), a single, pride-sopped loner with whom we come to love most. His colleagues range from Reina (a security guard with familial connections), Amador (a decrepit old man), Jose (a man whose marriage and manhood are slowly dying) and Lino (whose age keeps him from finding work).

While many of the men fight for work that they know will never come to them, all of them have found a common interest in drinking at The Shipyard, a local bar. The men all try, in their own ways, to get by and keep living. Whether it’s through playing the lottery, taking babysitting shifts from 15-year-old girls, stealing food from grocery stores or wearing their son’s clothes and dying their hair to look younger, the men dream of a day when they can be working again.

While at The Shipyard, the men bounce dream-like wishes off of each other. At one point, Santa becomes enthralled with Australia, a land he deems magical because it is twice the size and half the population of Spain. In another moment, Jose reflects on how great it must be to organize a TV program. They go on, talk some rubbish and live like kings.

Two separate, but equally poignant, moments in the film use blatant metaphors to show just how truly awful life can be. When Santa reads the story of the ant (earnest worker) and the grasshopper (lazy dreamer) to a 4-year-old he is babysitting, he explains to the child that some people are born grasshoppers and others are born with the opportunities of ants. Indeed, as all of the men eventually find out, their quest for life to be meaningful is a dead end. As with another metaphor, in the bathroom of The Shipyard the light switch is timed. When the time has come, the light goes out. The lives of these men work exactly as the lights do in the film. As is expected, when a light is to go out, so is one of their lives.

With the topical surface of “On the Waterfront,” this film takes the theme a step further. By going into the depressing lives of these men, and the alcoholism that ensues, the audience can realize how large of a canvas the director/writer (Fernando Le¢n de Aranoa) has just painted on. In nearly every nation, in every city across the world, men and women are being laid off and lives are being destroyed.

Bardem’s (“The Sea Inside”) versatility in this film is astonishing. His look and demeanor directly contrasts anything he has ever taken on. In Europe, “Mondays in the Sun” received many accolades; however, most acclaim went to Bardem and Aranoa.

If easily depressed or moody, this film may not be the one to see. However, the themes and topics the film takes on are as powerful as the ships the men once built. With Homecoming weekend as this film’s slot on the calendar, it may very well put a damper on drinking, to say the least.