More than a day off

What Labor Day really means

More stories from Lauren French

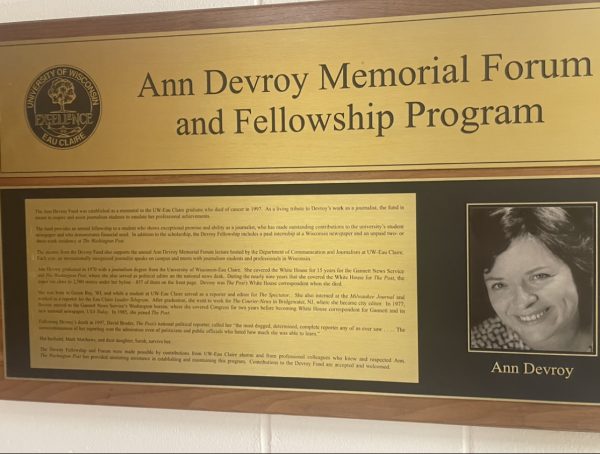

Photo by SUBMITTED

A New York City Labor Day parade in the 1960s. The parade tradition still continues today in large and small cities across the country.

For many modern Americans, Labor Day is a distinct seasonal landmark – it signifies the end of summer, the beginning of a new school year and the day fashion gurus decided it’s no longer OK to wear white.

On their day off, students and workers alike grab picnic blankets, cases of brats and some beer and trek to the nearest park to celebrate.

But what are Americans actually celebrating?

Long before it was known as the end-of-summer holiday, Labor Day had, and still has, an entirely different meaning. Labor Day’s origins delve deep into the roots of this country’s modern workplace: American labor and the power of collective bargaining.

Labor Day stretches back to the late 1800s, and its path is riddled with turmoil, strikes and even death. Labor unions across the country were trying to improve working conditions – the Economic History Association states typical workweeks in the 1800s were about 70 hours – and were met with government resistance.

Since then, the American workplace has come a long way. David Schaffer, an economics professor, said Labor Day is a chance to celebrate the role workers played in setting up the U.S., and should inspire young people to become involved in workers’ rights.

“It’s a general chance to honor people who went before you and did good things,” Schaffer said. “Hopefully, that will give you some incentive to do the same.”

Schaffer said Labor Day is important to students because unions have influence over wages, retirement insurance and health insurance options in fields students will be going into. Students can celebrate Labor Day by learning more about its history, or simply talking to relatives who are involved in a union, he said.

In some cases, students are already union members and chose to spend the Monday holiday celebrating the role their union has in their own workplace.

Senior political science major Anna Schwanebeck is one of those students.

Schwanebeck joined the United Steelworkers union when she started a summer job at a paper mill two years ago, and said the union gives her a sense of security in a potentially dangerous work environment.

Schwanebeck said Labor Day signifies the accomplishments workers achieved before her and serves as a reminder of how important unions are in keeping up workers’ rights.

Instead of using Monday as a typical day off, Schwanebeck said she made a point to attend Laborfest at Phoenix Park.

“It definitely doesn’t mean a day of rest for me, and it never really has,” Schwanebeck said. “It’s a day of pride, and it’s a day of refocusing on what … labor has done for this country.”

Schwanebeck said it’s hard for those who have never experienced a union to understand completely, but rural and factory workers shouldn’t be forgotten.

“We’re out there, and we’re all working really hard,” Schwanebeck said. “We’re all doing things that you benefit from, so it’s important not to forget that we’re there, and that our rights matter, too.”